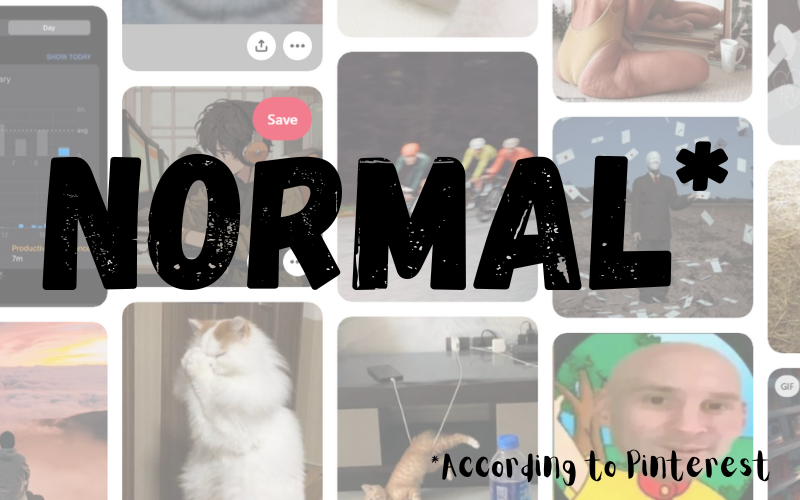

When I was younger, one of my deepest desires was to be… normal.

For me, that meant doing things with other people, like I saw on TV. Look at me, I’d think, at a sleepover like a normal person. This is good. Even if I could only cope with sitting on the stairs while everyone else hung out in the living room.

It has taken work to separate how I actually enjoy socialising from my desire to fit in and do things the ‘right’ way. Here are some social things I genuinely enjoy:

- A quest (any activity with a clear goal)

- Activities where I can easily leave (having an escape plan helps me relax)

- Having opinions on popular culture

- Long voice note messages (no pressure to respond immediately)

- Going to the cinema

- Someone making me nice food

- Sending and receiving interesting links

- Bird watching (an exhaustive list of birds I can identify: robins, magpies, jays, buzzards, some gulls, blackbirds, pigeons, oystercatchers, crows/rooks/jackdaws, choughs, red kites, and sparrows)

And here are things I eventually realized I don’t enjoy:

- Going to restaurants and having a conversation at the same time

- Conversations with more than one other person

- Going with the flow

- Competitive activities

- Activities requiring physical coordination (I don’t have any, and it frustrates me)

- Situations where I have to dress a certain way

These are just some of the ways my brain affects how I connect with others. I generally prefer social opportunities that are low on sensory input, structured, and free from pressure to achieve anything.

For everyone—neurodivergent or not—it can be helpful to reflect on the messages you’ve received from family, culture, and society about the ‘right’ way to have friendships and relationships. Comparing these with your values and what you genuinely enjoy can help you understand the conditions you need for relationships to thrive. If there’s little overlap between what you’ve been told you should want and what actually makes you happy, this mismatch can create stress, unhappiness, and a sense of “failing”—when really, you’re just different.

For others, ADHD, autism, or other neurodivergent traits affect socialising in different ways. Some challenges are practical—like sensory needs (low lighting, no background noise), difficulty remembering connections with people you don’t see regularly, or struggling to leave the house on time, making social plans feel overwhelming.

Other challenges are emotional. After a lifetime of feeling different, trying to be ‘normal’ can be exhausting. Suppressing stims for a few hours might not feel worth it. Past experiences of exclusion or rejection can make reaching out harder. Rejection may hit deeper, making avoidance seem safer. It can be difficult to trust that others will truly see and value you.

But neurodivergence can also bring strengths to relationships:

- You might be great at organizing and creating structure.

- You may bring energy and joy to social spaces.

- You might be consistent and dependable in ways others appreciate.

- You may articulate your needs clearly and be generous in supporting others.

- You might be spontaneous, responding creatively to situations and proposing new ideas.

Whatever your social preferences, whatever scripts you’ve absorbed about how relationships should work, and whatever past experiences you carry, reflecting on your needs and preferences can be valuable. It won’t magically solve everything—it can still be hard to find people who match your vibe—but knowing yourself is an important part of the equation. It’s less important what’s normal for others, and more important to find what works for you.