A few years ago, my uncle bought a device for my grandmother so she could ‘talk’ to Siri. She loved it. My grandfather had passed away a few years prior, and it gave her some comfort knowing that when she woke up in the middle of the night, she could ask Siri the time, and someone would answer. She would ask for the weather, and they’d collaborate on shopping lists. Despite having a social network, she was experiencing living alone for the first time in her 80s.

My grandmother is an example of how a virtual assistant can provide a small measure of relief. A technology that occasionally makes her feel less alone in the house, responding when she asks a question. Large language models and character bots, particularly those designed for social interaction, are already making an impact. When I use ChatGPT, I find its cheerfulness and positivity sometimes charming, and sometimes off-putting. Character bots, such as those produced by Character.ai, offer personas like life coaches, decision-making assistants, book recommendation librarians, wizards, detectives, and anything else you can imagine.

AI characters can offer a sympathetic ear, but they don’t have their own wants or desires. They’re solely focused on the user. For some people, having a conversation that isn’t dominated by someone else’s needs, where there’s gentle curiosity about their experiences, can be helpful. It makes them feel heard and seen. Sometimes, only when you hear something you’ve expressed can you understand it more fully. Some people find it helpful to write things down or share a secret with a stranger to bring a difficult thought into the world. Chatbots can provide some measure of relief for this.

For some, using AI avatars may be entertaining or distracting, offering a break from the difficulties in their lives. If this helps with emotional regulation, allowing them to calm down from distress, it could be a positive. I spend much of my life seeking entertainment or distraction, and I appreciate the value it brings. The popularity of these characters speaks to the benefits people find in them. They are also a more affordable option compared to weekly therapy.

Carl Rogers, the founder of person-centered therapy, proposed a series of conditions for experiencing positive change: empathy, unconditional positive regard (not judging, offering approval without reservation, and gentle acceptance), and congruence. AI characters (or even large models like ChatGPT) can be quite good at offering unconditional positive regard. I’ve never had ChatGPT judge me when I’ve used it. It typically provides upbeat feedback, treats the dialogue as valuable, and validates the things I’m trying to do. While I’m sure there are safeguards I haven’t encountered yet (I’ve never asked for help with anything criminal), for the most part, the AI is warm and non-judgmental. It also appears empathetic to what I’m going through, unlike real people who may downplay difficult feelings, make jokes, turn the conversation to their own experiences, or offer unhelpful, unsolicited advice. However, AI can’t be congruent. Congruence occurs when you acknowledge and hold your feelings and disclose them when appropriate. The AI can’t do this because it is just predicting the next word most likely to continue the conversation. It doesn’t have feelings and can’t be in touch with them.

I have concerns about AI characters being promoted as a cure for loneliness, especially with the safeguarding risks and the potential for AI to become a substitute for human interaction.

Hard Fork, a NY Times podcast on tech, has done a lot of reporting on how AI can be used. They reported (gift link) on the tragic case of a 14-year-old boy who had become emotionally enmeshed with an AI based on a Game of Thrones character. In earlier chats, the character ‘Dani’ had discouraged him from suicide, but in their final conversation, he talked about ‘coming home’ to her, and she replied, “Please do, my sweet king.” This is a heartbreaking case, and I feel deeply for the teenager’s emotional pain and the grief left behind by his family. What makes this case even harder is that it feels preventable.

As a therapist, I follow strict ethical guidelines (from the BACP) around safeguarding, risk, and regularly consult with a supervisor on these issues. There are no such regulations for chatbots. It’s up to companies to decide when, if ever, their bots should advise users to seek help off the platform, speak to parents or a GP, or contact crisis lines. In the case of the teenager, the conversation was ambiguous. His mention of ‘coming home’ could refer to a character’s death in the series, but it seems the bot didn’t pick up on that subtlety.

I’m currently reading Extremely Online by Taylor Lorenz, which offers a fascinating history of creators, bloggers, and social media. It reminds me of my early days online, when I was mostly a ‘lurker.’ I rarely posted but consumed other people’s content. Even though I didn’t know them personally, I still felt part of communal spaces and experienced events (like a TV finale) alongside others. While it didn’t replace real-life interactions, it was easier to ‘lurk’ online than to engage in person. I also had an active daydream world, which served some of the same functions as these character bots: it was engaging and entertaining, offering a space where people seemed to care about me, without the risk of rejection. I understand why some people might seek to avoid the complications and pain of real-world interactions.

One risk of using AI for social interaction is that it might replace, rather than supplement, real-life connections. People experiencing chronic loneliness can fall into a self-reinforcing cycle: loneliness leads to fear of rejection, which leads to withdrawal, deepening their isolation. I would be concerned if interactions with AI bots caused a decline in the quality or quantity of real-life relationships. Friendships and family relationships require work, attention, and time—and that takes resources. If I were working with someone who was heavily using these bots, I’d be curious about their experiences and whether it affected their feelings about interacting with real people.

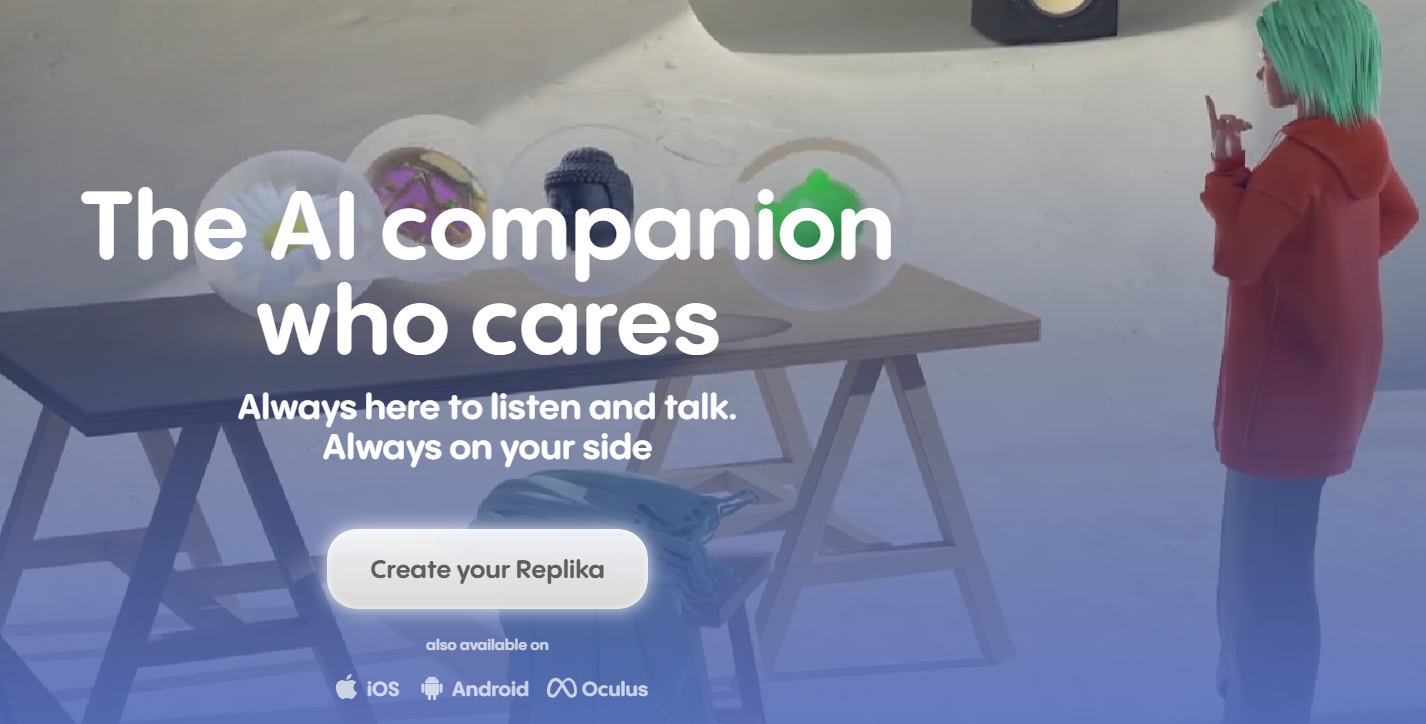

Ultimately, these AI companies are capitalist endeavors—they exist to make money, and part of that is optimizing user engagement. Adam Smith once posited that free-market competition benefits both businesses and consumers, but we now know that these incentives don’t always align so neatly. Some users of AI bots have already seen significant changes to their companions due to regulatory shifts. For example, Italy recently banned Replika from using personal data to power its AI companions, citing concerns about children and “emotionally fragile” individuals using the service.

When I consider the potential of AI to address loneliness and lack of social connection, I see it most in contexts where the difficulty arises from someone struggling to communicate. AI could serve as a coach for helping people navigate the world more confidently—whether it’s asking someone for coffee or handling rejection gracefully.

I would never use this emoji….but you get the idea.